“DINO sanguinem bibis et carnes manducas … sed collige ungulas centum et quinquaginta … dormi nunc et semper … Amen.”

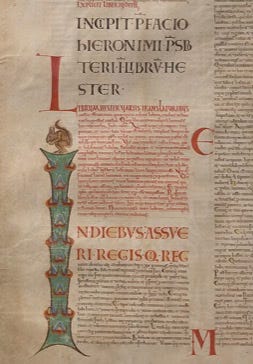

The Devil’s Bible, Codex Gigas, is the largest surviving medieval manuscript, created in 13th century Bohemia and famous for its full-page portrait of the devil (Knuth, 2007). An illuminated manuscript, the massive tome contains the Romanesque Latin Bible, together with secular and magical texts collated in one giant body. One of the most fascinating spells within the manuscript — often dismissed as nonsense by scholars — is, in fact, a brilliant example of spirit-binding magic, utilising the mechanism of counting compulsion.

To understand the thinking and technology behind the spell, we first have to unpack some of its magical thinking, within the context of medieval understandings of the supernatural world. In doing so, we are able to better appreciate both the historical usage and function of magic and enchantments, while enabling a reconstruction of its technique to our own sorcerous endeavours.

One of the aspects of the spell discussed here is the instruction to the spirit, DINO, to collect 150 claws. As will be shown, this isn’t an arbitrary nonsense contrived by uneducated folk or simple scribes, but a complex cultural knowledge of spirits and how to bind them. In this, we can reverse-engineer the spell to recover the essential formula.

The Spell

The spell under discussion is concerned with assuaging fever and it functions through identifying the spirit responsible, and binding it. This is not uncommon in medieval spells, such as the Old English medical charm Against a Wen (British Library Royal MS. 4A.XIV). Crucially, in this charm, the wen — a cyst or boil — is exorcised, and, like our fever-spirit spell, works by addressing the wen-spirit directly.

The relevant excerpt from the Codex Gigas, addressing Dino, is as follows:

“K X K Pat. Credo… DINO sanguinem bibis et carnes manducas … sed collige ungulas centum et quinquaginta … dormi nunc et semper … Amen.”

Translation:

By the cross, by the cross, Paternoster, and the Credo. Dino: you drink blood and eat flesh … but collect 150 claws … sleep now and forever … Amen.

It would, at first glance, appear clear to the modern or scholarly eye that the spell is absurd, lacking in a sensible or cohesive structure. However, to a sorcerous eye, the logic is clear:

This isn’t metaphor—it’s a trap.

Why 150 Claws?

In traditional magic, spirits are compulsive counters. This belief appears across cultures. For example, vampires must count spilled rice or seeds (Barber, 1988), djinn get trapped in knots (El-Zein, 2009), and European demons are delayed by salt or seeds scattered across thresholds (Frazer, 1922).

Thus, commanding Dino to “collect 150 claws” isn’t a request — it’s an impossible compulsion. The spirit becomes caught in a recursive task, unable to complete its attack, essentially suspended by its own programming. In this way, the spirit becomes ensnared, entangled in a repetitive and seemingly endless duty that it is compelled to fulfil. Similar beliefs are found in the classic spirit trap, whereby shiny objects might attract the spirit, where a tangle of knots, many threads tangled randomly together, with a number of other items that must be counted, all work of the same technology.

The choice of the number 150 suggests that it is just large enough to be overwhelming, but also may echo the 150 Psalms in the Vulgate Bible — a spiritual counterweight to disease.

Structure of the Spell

This isn’t a random jumble of words. Like most medieval charms, it follows a deliberate structure:

1. Opening Invocation

K X K Pater. Credo.

Establishes ritual authority via Christian formulae.

2. Naming the Spirit

DINO sanguinem bibis…

Naming grants power — to name is to bind.

3. Binding Task

Sed collige ungulas centum et quinquaginta…

A task that locks the spirit into its compulsion.

4. Dismissal

Dormi nunc et semper…

Not a banishment — an eternal dormancy.

This pattern appears frequently in medieval grimoires and folk charms, including those in the Munich Manual and Pseudo-Albertus Magnus (Kieckhefer, 1998).

Related Spell: The Seven Sisters

Another fever charm in the same manuscript invokes the Seven Sisters of Satan — an allegory for feverish illness:

Adjuro vos, sorores infernales, per sanguinem Christi, per Martyres et Prophetas, per crucem sanctam: exite ab infirmo servo Dei. Dormite nunc, sicut agnus anniculus.

Translation:

I adjure you, sisters of hell, by the blood of Christ, by the martyrs and the prophets, by the holy cross: depart from the sick servant of God. Sleep now, like the yearling lamb.

This is a Christological binding formula, using layered names and sacred authority to induce dormancy in demonic personifications of disease.

As with Dino, there is no violence here, more a compulsion or charge with an impossible task. Medieval folk magic wasn’t random, it contained logic and internal rules, often involving compulsion, naming, distraction, and impossibility. Similarly, the medieval worldview was not symbolic, it was functional. As can be seen in the fever-spell, the disease is a spirit, and words are tools. The incantation texts of the Codex Gigas demonstrate a magical operating system, using logical premises and techniques that enabled charms and formulas to be seen, to an inexperienced eye, as random nonsense, coupled with superstition — a word which is often used to imply simplicity, and the unintelligent. The language of the spell points to complex thinking, the use of naming and impossible tasks, the handling of spirits in a spirit-filled world. Demonstrably, medieval and folk magics were not simple rustic nonsense, but sophisticated and intelligent formulae, that still work.

In analysing the technique of the magical charm, it becomes apparent that the logic and ethos are perfectly sound and aligned to a magical worldview that has distinct guidelines — not ambiguous, capricious or random, but subscribing to certain formulae. These formulae are evidently ancient and embedded within culture and folklore through utility rather than scholasticism. These are time-tested techniques of sorcery in a spirit-filled world, learnt and passed on by experience. Even during the high medieval period, when manuscripts and writings were mostly the reserve of the monastic scriptorium, the magical formulas were preserved in texts, such as the Devil’s Bible.

That the use of incantations and charms such as these might be regarded as illicit, and their appearance within the Codex Gigas following a large image of satan is a conundrum for some academics studying the manuscript. It is widely suggested in some learned circles, for example, that the charms here are a type of counter to the invoking of the adversary through the image in pages following the text. This, however, feels like a reach, an attempt to connect the depiction of the devil with the more unauthorised magical writings that don’t belong to an accepted, orthodox body of literature.

It is just as likely that the charms appear alongside satan as they do belong to a world in which such things coexist, rather than the strict doctrinal rules of the church ceremony and ritual, or official writings approved by authorities. These conjurations are outside of the formal ecclesiastical rites, albeit adjacent in a broader purview. We should remember that the Catholicism of the medieval period was a relatively magical religion, especially by comparison to early modern and later Protestentism. That being said, the incantations of the Codex Gigas are a departure from the accepted writings that represent something of the high wisdom of the age. Belonging to a range of magical thinking, of illicit magics, and somewhat folkish (that is, characteristic of the ordinary people), the inclusion suggests a more humane and rounded aspect that fleshes out something of the character of the scribe or scribes who chose to commit time, effort and resources to preserve the incantations in a giant book.

The use of spells and charms by clerics and clergy permeates the late medieval and early modern periods, giving rise to the ‘conjuring parsons’ who worked alongside, and often as, cunning folk into the 19th century — especially in the West Country (England). The availability of writing, magical literature and formulae, familiarity with psalms and religious liturgy, made these rural priests highly attuned to a magical world.

With the dominance of the protestant faith in England, for example, all things ‘popish’ (Catholic) became resigned to the class of magical works. Such circumstances resulted in charges against the Pendle witch called Demdike who had inherited magical family charms derived from Catholic Latin, damning her as a witch and recusant both! The use of charms and psalms in folk Catholicism is well-established, and was commonly associated with magic and witchcraft in the early modern period. Even the Elizabethan court magician John Dee had received all six Catholic holy orders during the reign of Queen Mary, before being ordained in the Anglican Church when the protestant Elizabeth I came to the throne.

It should be remembered, too, that many of the grimoires would have been preserved and passed on through the scriptorium that predominantly belonged to monastic orders until the 14th century, after which secular and commercial workshops also arose. Inevitably, this meant that the priestly class were amongst those likely to possess, compose and use the rituals of magic, conjuration and demonology. Indeed, many grimoires and formulae require a degree of religious purity, through prayer and fasting, confession and expiation — the Abramelin ritual being one such example.

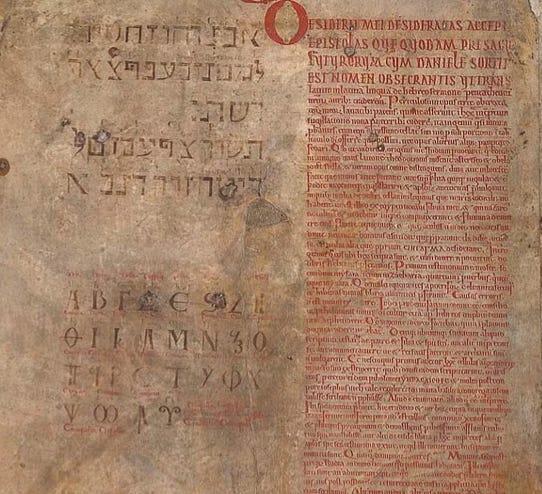

Therefore, it may seem surprising that a bible manuscript would contain conjurations and charms, but the reality is that it is part of a greater perspective. The Devil’s Bible is an attempt at a complete collection of wisdom, and — aside from the Latin bible — contains many works, including Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae, medical works, Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews and Jewish Wars, along with various alphabets and a calendar. The inclusion of appeals to spirits, in Christ’s name, and magical binding formula are a positive part of the medieval mindset.

This post sets out to explore the ethos and practical workings of traditional magic — how it functions, why it endures, and, importantly, how it might be made relevant in the modern world. My aim is to delve more deeply into some aspects of magical practice, beginning with this broader discussion and continuing through a series of future articles that could potentially offer detailed instructions, reflections, and rituals where appropriate.

That said, it only makes sense to share such work when there is genuine interest and a sincere will to engage. As the series progresses into more esoteric or practical territory, some of these deeper explorations may be placed behind a paywall — not to restrict access arbitrarily, but to preserve the integrity of the work and to honour the commitment of those who choose to take it seriously.

Sources & Suggested Reading

• Barber, Paul. Vampires, Burial, and Death: Folklore and Reality, Yale University Press, 1988.

• Brock, Sebastian P. “Charms in Syriac Medical and Other Texts.” In Magic and Magicians in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Time, De Gruyter, 2013.

• Davies, Owen. Cunning-Folk: Popular Magic in English History, Hambledon, 2003.

• El-Zein, Amira. Islam, Arabs, and the Intelligent World of the Jinn, Syracuse University Press, 2009.

• Frazer, James G. The Golden Bough, Macmillan, 1922.

• Kieckhefer, Richard. Forbidden Rites: A Necromancer’s Manual of the Fifteenth Century, Penn State Press, 1998.

• Knuth, Rebecca. Burning Books and Leveling Libraries: Extremist Violence and Cultural Destruction, Praeger, 2007.